I haven’t written much about recovery lately. Not because it’s gone away, but because the story hasn’t really changed – it’s the same one, just with more adjustments layered on top. Since having Covid, I’ve been hovering in a kind of superposition: recovering, and simultaneously not recovering.

I’m aware of the box, and I know what opening it would mean. Part of me avoids it because ED thoughts still have enough presence to scare me away. But just as much, my body has forced a hard stop of its own – exhaustion so deep that I don’t even have the capacity to cross the room and open it, even if I wanted to.

I also know I’m on a knife edge physically and mentally. Any obstacle while pushing this recovery rock up the hill could send it tumbling back down on top of me. And sometimes Sisyphus needs to gather his strength – because a disabled Sisyphus is limited not just by will, but by physical capacity. When the hill feels less like an escalator and more like the travelator from Gladiators, waiting and stabilising isn’t giving up. It’s the only sensible option right now.

The Knife Edge

I’m currently slightly above my lower set weight, which sits within a healthy BMI. Most of the time, my body is reasonably comfortable. It functions about as well as it can, given my conditions, perimenopause, and everything else that comes with that. Hormone regulation isn’t something I can rely on at this stage – unpredictability is just part of the picture now.

My hunger cues are chaotic, but that isn’t new. There still isn’t a clear “full” signal unless I’m ill, and that has always been my baseline. Importantly, my body isn’t urging me to gain more weight right now. I haven’t experienced extreme hunger for months.

And yet, I know this peace is fragile – as sharp as a knife’s edge.

When I caught Covid, I lost weight through illness and, ironically, had a clear fullness signal for once. My body struggled with that drop. It panicked. Strong, persistent hunger returned – not extreme hunger (those get conflated far too often), but intense hunger nonetheless. At the same time, my metabolism dropped significantly, something MacroFactor’s algorithm picked up clearly. Once I regained the weight I’d lost and adjusted my intake to reflect my new, lower post-Covid maintenance, things settled again.

Until they didn’t.

I wrote recently about a trip to Cardiff. It involved far more activity than I’m used to – and more than I should have attempted during a post-viral flare. Pushing beyond my current capacity aggravated my chronic fatigue syndrome, and I’ve been stuck in post-exertional malaise ever since: fog, severe fatigue, and chronic pain, now five days on. That increase in activity, combined with eating at my already-lowered maintenance, triggered another bout of intense hunger that lasted three days (I don’t regret Cardiff though, I loved supporting my son, would overdo it again just for him).

That’s when the knife edge became impossible to ignore.

I know how to step away from it. The most reliable way is to gain weight toward the middle of my set range, where my body has more buffer and doesn’t react so sharply to stress or illness. My instinct was to fix this immediately – to solve it now, while I could see the problem so clearly.

But my chronic fatigue and post-exertional malaise won’t allow that.

From a mental health perspective, the best thing would be to get the weight gain over with – to move myself off the knife edge and quiet the constant vigilance. But physically, that would be one of the worst things I could do right now. Adding weight means more stress, more digestive demand, more work for a body that’s already struggling. That would mean more fatigue, more pain, less ability to move – and ironically, worse mental health, not better. It’s depressing to have done nothing all day except try not to fall asleep… again.

I don’t get the luxury of working on my mental health in isolation. My physical health doesn’t allow it. So I’m taking a pause and waiting for this flare to subside before pushing my recovery rock any further.

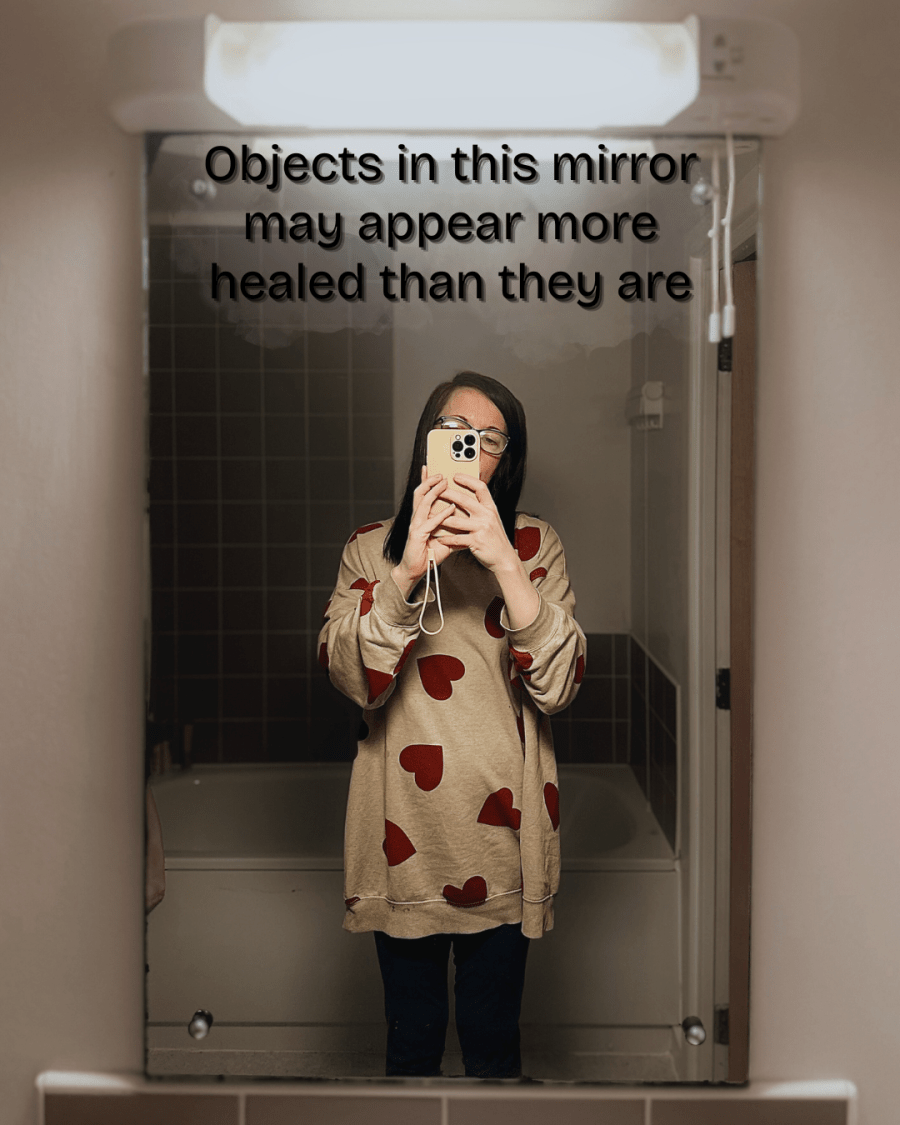

Objects in the Mirror May Appear More Healed Than They Are

I’m in a strange mental place with recovery too. I look healthy, and because I’ve deliberately gained muscle this time, I also look strong. Last time, when I did all-in recovery, I still had muscle atrophy at this weight and looked visibly frail. Not this time.

If I’m Sisyphus pushing my recovery rock up the hill, I look highly capable of doing it. I’ve built quads and traps – the exact muscles responsible for pushing a giant rock uphill.

But the battles taking place in my head are invisible, and no one would assume I’m even having them. I’m struggling deeply with how my body now looks strong while remaining physically incapable. I worked hard in this recovery to rebuild my body. I eat well. I take creatine. I’ve gained muscle. And yet it still can’t cope with a trip to Cardiff without days of post-exertional malaise, chronic pain, and brain fog so severe that I’m on attempt three at writing this blog post (hopefully third time’s the charm).

There have been nights spent staring out of rainy windows, crying at the realisation that hard work can force my body several steps backwards – and that building capacity again means starting from zero, more slowly, after my body has pulled a hard stop. Chronic fatigue is like that. You think you’re getting somewhere, and then it flares, and you’re back to trying not to fall asleep after dinner because eating used up all your spoons and now you have none left.

Some of this grief comes from beliefs I absorbed. There’s a pervasive idea online that if you just eat right and do all the right things, mental illness and physical health problems will resolve. Despite knowing better, I wanted to believe that. It’s easier than acceptance. The truth is that I’m not better in the way I hoped I would be. The work I’ve done has made a difference – but in a flare like this, that difference isn’t visible. It’s not currently observable.

That makes the mental health side of recovery incredibly difficult. I’m not physically well enough to tackle it – and I’m not mentally well enough either, because I’m grieving that reality. Clippy (my ED) tries to take advantage of that vulnerability. It sings its familiar, distorted tune about how I can’t control anything – but it knows a way I could. I ignore it as I grab another protein shake.

Dealing with Clippy is horrendous, and I have deep empathy for anyone fighting their own version. But right now, I wish that was the only battle I was facing. People often talk about recovery in terms of finding yourself and discovering purpose – but when your life is constrained by other conditions, dreaming of a future that isn’t physically obtainable can be dangerous. Maybe my recovery, at least for now, is acceptance. Not striving for a future that doesn’t exist, no matter how hard I work.

Hard work backfires in fatigue conditions. Slow, graded movement forward is safer. I’m learning that my recovery has to follow the same rules – even when every part of me wants to push harder.

One Must Imagine Sisyphus Happy.

I’ve struggled with chronic fatigue since my son was born – whether from pregnancy itself or the glandular fever I had when he was around six months old. I’ve struggled with eating disorders and my mental health even longer. And yet, I’ve had a life full of love and meaning. I have a wonderful relationship with my son. I’ve had life-altering, soulmate-type friendships. I’ve found meaning through physics, art, writing, video games, and more recently, philosophy. I’ve even found meaning in my struggles by sharing them honestly.

But comparison is the thief of joy – and meaning.

Recovery narratives online have the same problem I have with Christmas. When you don’t have family beyond your child, and you’re bombarded for two months with big family Christmases on TV, in songs, everywhere, you start noticing what you’re missing – what everyone else seems to have that you don’t. It’s hard for Sisyphus to be happy if he’s pushing a giant rock while comparing himself to someone carrying a pebble up a hill they can slip into their pocket.

But Sisyphus can be happy if he focuses on his own rock.

I think that’s what acceptance really is. It isn’t giving up, and neither is it refusing to push or going above and beyond what you’re capable of because someone else tells you, “Well, it’s easy for me – maybe you’re just not working hard enough.” It’s focusing on your own rock and pushing it anyway, because pushing it is the point. That’s where my meaning comes from.

That doesn’t mean I won’t still cry while staring out of rainy windows, grieving the life I imagined that doesn’t exist.

I did that not five minutes ago.

Indeed acceptance is the key… Resentment causes so much imbalance… especially on this planet of duality.🪷

LikeLiked by 2 people